- Date: December 4, 2007

- Author: Joe Stewart

On the weekend of October 27, 2007, the Internet was suddenly bombarded with a rash of spam emails promoting U.S. presidential candidate Ron Paul. The spam run continued until Tuesday, October 30, when it stopped as suddenly as it began. At the same time, political blogs began to light up, accusing the campaign (or at least its ardent supporters) of running a criminal botnet for political purposes. We decided to cut through the spin and take a closer look at this botnet to determine its origins and shine some light on who might be responsible.

Tracking the Spam

Tracking specific spam back to a particular piece of botnet malware is somewhat challenging, but given the right cooperation between researchers who hold different pieces of the puzzle, it can be accomplished. To start, one must identify key characteristics of the spam that define a "fingerprint" of the email sent by the bot. Although senders, subjects and email bodies will vary from spam to spam, often the email headers contain certain static elements which are unique to the mailer engine in the bot software.

In the case of the Ron Paul spam, we were able to identify these key elements:

- The initial "Received" header is always of the format "from [bot ip] by [nameserver of alleged sender domain]"

- The Message-ID always begins with three zeros and ends with a random string of lowercase letters

- The dates in the headers are always shown in GMT time, regardless of the local time zone of the bot

- The X-Mailer is always Microsoft Outlook Express 6.00.3790.2663

- The X-MimeOLE version is always Microsoft MimeOLE V6.00.3790.2757

By looking for emails containing these hallmarks, we were able to quickly track several thousand IP addresses sending Ron Paul spam during the time period above. We were also able to see the other types of spam being sent by the botnet - quickly dismissing the idea that this botnet was created for the purpose of political spam. Emails emanating from the botnet pitched all of the usual spam products, from pharmaceuticals to fake watches.

Getting the Malware in Hand

At this point, armed with the IP addresses of current bots, it is possible to trace the command and control server of the botnet with cooperation from network administrators who have bots on their network. By monitoring and correlating network flows, the command center was soon tracked to a server at a co-location facility located in the U.S., one that is well known to malware researchers as a frequent host of this type of activity.

These clues also led us to the name of the malware behind the botnet - Trojan.Srizbi. Based on this we were able to locate several variants for testing, the earliest one having been compiled on March 31, 2007. At the end of June, Symantec wrote a fairly detailed blog entry about Srizbi. Information concerning technical details of Srizbi and its removal is available from various anti-virus firms, and will not be covered here.

How Srizbi is Spread

Analysis of recently compromised machines indicated that Srizbi is being spread by the n404 web exploit kit, through the malicious site msiesettings.com. This is a well-known "iframe affiliate" malware install site, where the site owner gets paid by different botnet owners for spreading their malware. A trojan is installed by the exploit kit which regularly requests a remote configuration file containing URLs of additional malware to download and install. Previous reports have implicated the use of the MPack web exploit kit in spreading Srizbi as well, so it seems this is the Srizbi author's preferred method of building the botnet.

Unfortunately for Srizbi's author, this approach may have some drawbacks - one machine we analyzed was infected with no less than nine other spambots, belonging to the malware families Ascesso, Cutwail, Rustock, Spamthru, Wopla and Xorpix. While installing multiple spambots may increase profits for the web exploiter, it forces the different spam engines to share resources and bandwidth. Some of these spambots utilize a great deal of CPU time and memory, which means not only is the system less efficient for the other spammers' use, but may force the victim to seek technical help to fix their "slow" machine, leading to premature removal of the bots. It also is likely to land the IP address of the infected machine in DNS blocklists much faster, rendering the bot much less effective in bypassing spam filtering.

The Reactor Core

With the help of Spamhaus, we were able to not only shut down the command and control server, we were able to obtain the running software from the server, written in the Python language. Examining these showed that the Srizbi botnet is actually a working component of a piece of spamware known as "Reactor Mailer". Reactor Mailer has been around at least since 2004, and is in its third major version. Versions 1 and 2 likely used proxy servers to relay the spam; however, since this is not as efficient as template-based spambots, version 3 was created along with Srizbi, the bot that actually does the mailing.

Reactor Mailer is the brainchild of a spammer who goes by the pseudonym "spm". He calls his company "Elphisoft", and has even been interviewed about his operation by the Russian hacker website xakep.ru. He claims to hire some of the best coders in the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States, the post-Soviet confederation) to write the software. This claim is probably true by examining details in the source code, we were able to identify at least one of the principal coders of Reactor 3/Srizbi, a Ukrainian who goes by the nickname "vlaman". Various postings by vlaman indicate he is proficient in C and assembler, and would certainly be capable of writing the Srizbi trojan.

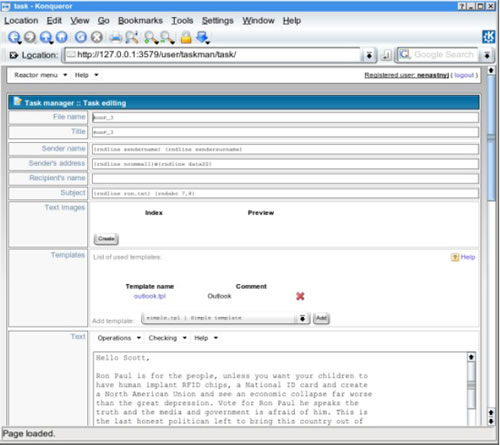

Reactor Mailer operates with a software-as-a-service model. Spammers are given accounts on a Reactor server, and use a web-based interface to manage their spam tasks. In the case of the Ron Paul spam, there was only one account on the server in addition to spm, which was named "nenastnyj".

We loaded the Reactor Mailer software onto a test machine in order to recreate the interface as seen by the spammer:

Although the spamit.com logo is displayed on the interface, there does not appear to be any association between the Reactor software and the real spamit.com website, which is a portal for Canadian Pharmacy spam affiliates. However, customers of Reactor Mailer do sometimes send spam for Canadian Pharmacy, as do most of the botnet spam mailers we've looked at. It could be that spm was contracted to develop the Canadian Pharmacy portal, however, there is also a personality on bulkerforum who goes by the name spamit and claims to be in the pharmaceutical spam business, so we do not believe spamit.com and spm are the same entity. The real spamit.com affiliate portal is shown below:

The Ron Paul Job

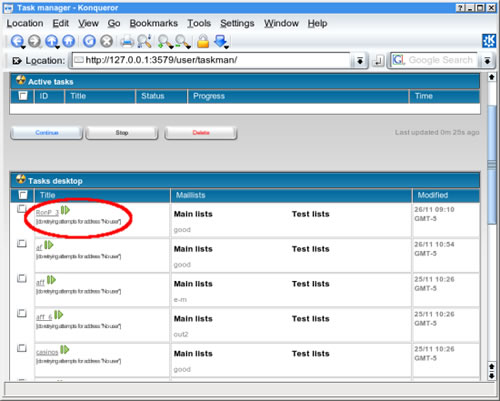

Upon logging into the Reactor Mailer interface, the spammer is presented with a list of saved tasks. In the screenshot below, we can clearly see a task called "RonP_3".

Clicking on this task link gives us confirmation that the spammer calling himself nenastnyj did indeed send the Ron Paul spam:

The list of email addresses assigned to the RonP_3 task is simply titled "good". In the backend Reactor files, this file is 3.4 gigabytes in size, and contains 162,211,647 email addresses. Although this is a substantial number of email addresses, many of these are certainly outdated or invalid addresses. However, Reactor, like many modern spam botnets, has a feedback mechanism to allow the controller to know when emails are rejected. It cannot tell however, when emails are accepted by the destination mailserver and then bounced later. As a result, organizations who do "accept-then-bounce" are likely to have a higher email load, since they never manage to have outdated addresses purged from botnet spammer mailing lists, and they spend a lot of time and bandwidth bouncing emails back to domains that were spoofed by the spammer.

While the total count of Ron Paul spam messages that actually landed in peoples' inboxes can't be known, it certainly was received by millions of recipients. All this was done using around 3000 bots this speaks to the efficiency of the template-based spam botnet model over the older proxy-based methods. The front-end also plays a part in the efficiency, by allowing the spammer to check the message's SpamAssassin score before hitting send, simplifying the process of filter evasion and ensuring maximum delivery for the message.

Mapping the Reactor Operation

Since the bot uses a specific TCP port to communicate with the controller, it is possible to locate additional botnet controllers at the same co-lo facility. By checking nearby network addresses, we were able to map out 16 additional servers controlling different variants of the malware. Communication with these servers showed that the botnet is segmented so that each sub-botnet is probably rented to different customers.

The servers we mapped showed the following activity:

xxx.xx.168.107 - Inactive

xxx.xx.168.134 - Penis pill spam

xxx.xx.168.137 - Russian-language spam

xxx.xx.168.143 - Inactive

xxx.xx.168.144 - Inactive

xxx.xx.168.250 - Previously used, down now

xxx.xx.169.2 - Inactive

xxx.xx.169.22 - Replica watch spam

xxx.xx.169.25 - Russian-language spam

xxx.xx.169.107 - MLM work-from-home spam

xxx.xx.169.110 - OEM software spam

xxx.xx.169.135 - Work-from-home spam

xxx.xx.169.136 - Penis pill spam

xxx.xx.169.147 - Penis enlarge patch spam

xxx.xx.169.148 - Penis pill spam

xxx.xx.169.153 - Replica watch spam

xxx.xx.169.154 - Replica watch spam

Detection

Srizbi can be detected in operation on a network by the following Snort signatures:

alert udp any 1024: -> any 4099

(msg:"Trojan.Srizbi registering with controller"; dsize:20; content:"|2d|"; offset:6;

content:"|2d|"; distance:6; within:1; classtype:trojan-activity;

reference:url,www.secureworks.com/research/threats/srizbispam; sid:100000001; rev:1;) alert tcp any any -> any 4099 (msg:"Trojan.Srizbi requesting template"; content:"GET|20|/"; depth:5; content:"|0d0a|X-Flags|3a20|"; within:200; content:"| 0d0a|X-TM|3a20|"; within:20; content:"|0d0a|X-BI|3a20|"; within:20; reference:url.www.secureworks.com/research/threats/srizbispam; sid:100000002; rev:1;)

Conclusions

With the facts above, we are left asking the question, "who paid to have the Ron Paul spam sent and how did they connect with the spammer, 'nenastnyj'?" The evidence shows that despite being capable of sending upwards of 200 million messages a day, nenastnyj is not one of the major spammers of the world, and seems to focus on spamming as an affiliate for larger "kingpin"operations. The Ron Paul spam was very much a 'one-off' job among the other tasks in the Reactor interface. It almost seems as though there may have been some pre-established relationship between the sponsor of the spam and nenastnyj. However, given the current state of law enforcement activity concerning spam in the countries of the CIS, it is unlikely we will get an answer to these questions. However, it does give us an unprecedented look at both the front and back-end operation of a modern botnet spam system.

SecureWorks would like to thank our colleagues at myNetWatchman, IronPort and Spamhaus for their invaluable assistance in the investigation of this botnet.