Summary

Since at least 2010, the IRON LIBERTY threat group (also known as TG-4192, Energetic Bear, Dragonfly, and Crouching Yeti) has targeted the energy sector with a particular focus on industrial control systems (ICS). Following public disclosures in 2014, the likely Russian government group became less visibly active, but by 2016 it resumed operations with a combination of new and old techniques and tools. Secureworks® Counter Threat Unit™ (CTU) researchers' in-depth analysis of the group's capabilities and targeting revealed an evolving threat to the energy sector and ICS systems, and to the defense and nuclear industries.

Background

In mid-2014, a number of public disclosures by security researchers highlighted the activity of a threat group that CTU™ researchers refer to as IRON LIBERTY. This group had been active since at least 2010. Although its targeting was broad, it had a specific interest in the energy sector, including energy companies and organizations financing the energy sector, in the U.S. and Europe. The longevity of the threat group's campaign, the nature of the targeting, and active development of a custom toolset strongly suggested the group was resourced and operated by a government. Technical indicators coupled with IRON LIBERTY's focus on the energy sector, especially in Europe, led CTU researchers to assess that IRON LIBERTY was likely operated by or on behalf of the Russian government. This focus on energy organizations, including suppliers, could align with Russian government intelligence priorities in support of its energy export-based economy.

Prior to 2014, IRON LIBERTY used custom malware, primarily Sysmain, Havex, and xFrost (now known as Karagany), combined with commodity penetration testing and tools. IRON LIBERTY was known for compromising targets via strategic web compromises (SWCs) using a custom exploit kit, through spearphishing campaigns, and by trojanizing legitimate installers that are then hosted on legitimate vendor app stores. In 2014, the group embedded Havex into legitimate remote management software for ICS and created industrial control scanning and enumeration modules.

Public disclosures in 2014 revealed likely IRON LIBERTY activity. The group was reportedly involved with breaches of Norwegian oil and gas companies. It was also deemed responsible for similar compromises in the U.S., the UK, and Canada. CTU researchers assessed that IRON LIBERTY's goal was to gather intelligence on the energy sector (particularly in Europe) to assist Russian government and corporate decision-making, and to gain access to energy-linked ICS for early-stage reconnaissance and potentially as pre-positioning for sabotage operations. Government-affiliated threat groups are typically not deterred by public disclosures, so CTU researchers expected IRON LIBERTY to reemerge with new malware and infrastructure.

The plugins deployed by Karagany malware compiled in 2018 contain links and similarities to tools used by the IRON LYRIC threat group (also known as TeamSpy) in 2012 and 2013, suggesting that IRON LYRIC and IRON LIBERTY share at least some of their codebase. IRON LYRIC was last active in 2013, and CTU analysis suggests that it was operated by a Russian intelligence service. The group covertly installed the TeamViewer desktop-sharing tool to surveil individuals.

The CASTLE campaign

In May 2017, CTU researchers began tracking a campaign that used spearphishing and SWCs to target the energy sector. Although the campaign was similar to earlier IRON LIBERTY operations, there were no technical links to IRON LIBERTY. As a result, CTU researchers assigned the name CASTLE to the cluster of activity identified in this campaign. Some reporting indicates that the CASTLE campaign began as early as December 2015. By late 2016, it was in full swing.

Reminiscent of IRON LIBERTY's 2010-2014 activity, the CASTLE campaign used compromised energy sector websites and spearphishing emails tailored for the energy and ICS industry to target individuals working in those sectors (see Figure 1). In contrast to the earlier activity, CASTLE did not install malware on the victim's system. Instead, it employed a technique that tricked the victim's system into making an SMB request to a CASTLE-controlled server, allowing CASTLE to harvest the logged-in user's account name and NTLM password hash sent with the request. Media reporting indicated that the threat actors modified an open-source tool called Phishery to perform template injection, in which the spearphishing email tricks the target system into requesting a remote template via SMB. The harvested credentials could allow the threat actors to access the target environment via single-factor authenticated Internet-facing services such as terminal services, a virtual private network (VPN), or corporate webmail.

Figure 1. CASTLE spearphishing lure document. (Source: Secureworks)

Linking CASTLE to IRON LIBERTY

The UK's National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), the United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT), and Symantec link the CASTLE campaign to IRON LIBERTY. Specifically, Symantec detailed the threat group's use of the Trojan.Heriplor malware. CTU researchers' comparison of Heriplor to an IRON LIBERTY Havex second-stage malware sample from 2014 revealed that the two samples wrote identical files and shared a command and control (C2) server, suggesting that Heriplor was developed from the Havex code base. CTU researchers have no evidence that other threat actors have used Havex or Heriplor.

CTU analysis has not revealed additional evidence linking CASTLE to IRON LIBERTY, but there is no reason to doubt these third-party assessments. The similarity in targeting and execution to previous IRON LIBERTY campaigns led CTU researchers to assess that CASTLE was likely a continuation of IRON LIBERTY's activities and was directed by the Russian government. Figure 2 shows a timeline of IRON LIBERTY activity between 2010 and 2018.

Figure 2. IRON LIBERTY timeline. (Source: Secureworks)

2017-2018 intrusion activity patterns

In 2017 and 2018, CTU researchers observed two distinct patterns of IRON LIBERTY intrusion activity: access intrusions and full intrusions.

Access intrusions

The first pattern seems to be designed to obtain persistent access to the targeted network through account compromise and without much use of malware. For example, IRON LIBERTY used credentials obtained by capturing SMB requests to obtain access in the CASTLE campaign. IRON LIBERTY used stolen credentials and connected to systems using Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) tools.

Post exploitation, the threat group used open-source tools such as the CrackMapExec penetration testing toolkit, the Mimikatz credential-theft tool, the Angry IP Scanner IP address and port scanner, and the PsExec Windows Sysinternals command-execution tool to move around the network. In one incident, the threat actors were able to acquire domain administrator credentials that allowed them to log on to the target's hypervisor, granting them full access to its virtualized servers. IRON LIBERTY makes efforts to remain undetected in a target network using tactics such as modifying the configuration of antivirus tools to prevent detection of malware deployed to the network.

To establish persistent access to a network, IRON LIBERTY created malicious LNK files on file shares commonly accessed by the target organization's employees. When a user's system mounts these shares, the LNK file makes an external SMB request with the user's username and NTLM password hash to an IRON LIBERTY server. This data provides the threat group with a constantly updated list of credentials. For additional access to a target network, IRON LIBERTY has installed web shells on a target's Microsoft Exchange server. The Z_webshell is written in ASPX and seems proprietary to this threat group.

Full intrusions

This pattern involves full exploitation of systems on the target network to steal information for espionage purposes. CTU researchers have observed IRON LIBERTY using this pattern during intrusions targeting energy, nuclear, and defense organizations. CTU researchers have been unable to confirm the initial access vector for these full intrusions. The threat actors may have used access intrusions against a related organization, such as a supplier, or may have leveraged a trojanized Adobe Flash installation file. In at least one case, a user was served an installer from what appear to be valid Adobe Flash download URL. However, the size of the data download was larger than the file that was saved to disk, suggesting that malicious content may have been served alongside the legitimate installer. The trojanized installer may have self-modified shortly after execution to remove all but minute traces of the malicious content, leaving only a legitimate Adobe Flash installer binary on disk.

After establishing initial access, IRON LIBERTY typically deployed the Karagany malware. In many cases, the threat group also used the MCMD remote access tool to download and install the open-source SoftEther VPN application. By using legitimate VPN software to set up TLS-encrypted bridges from its C2 infrastructure to target systems, IRON LIBERTY was able to hide its network traffic without deploying additional custom malware. IRON LIBERTY has also used compromised service accounts to access systems in order to install and upgrade Karagany malware, sometimes remotely via PsExec.

In several cases, IRON LIBERTY executed ProcDump via PsExec to dump the lsass.exe (Windows Local Security Authority Subsystem Service) process shortly before installing Karagany on a target system. This process dump contains all hashed account credentials, including credentials for the primary user and potentially for administrator and service accounts. These credentials can then be cracked locally using Mimikatz or removed from the environment for offline cracking. CTU researchers observed these process dumps being compressed with rar.exe, which aligns with an intent to exfiltrate the files for offline password cracking. IRON LIBERTY leveraged these credentials to hide its intrusion activity. Installing and running malware in the context of the system's primary domain user is less likely to stand out than repeated use of compromised service accounts across multiple hosts.

The threat group's malware is also designed to hamper incident response analysis. Karagany deletes unneeded plugins and files, although evidence of staged exfiltrated data can sometimes still be identified forensically. The C2 servers for the MCMD malware includes a self-destruct script that attempts to wipe evidence of the tool from the compromised system.

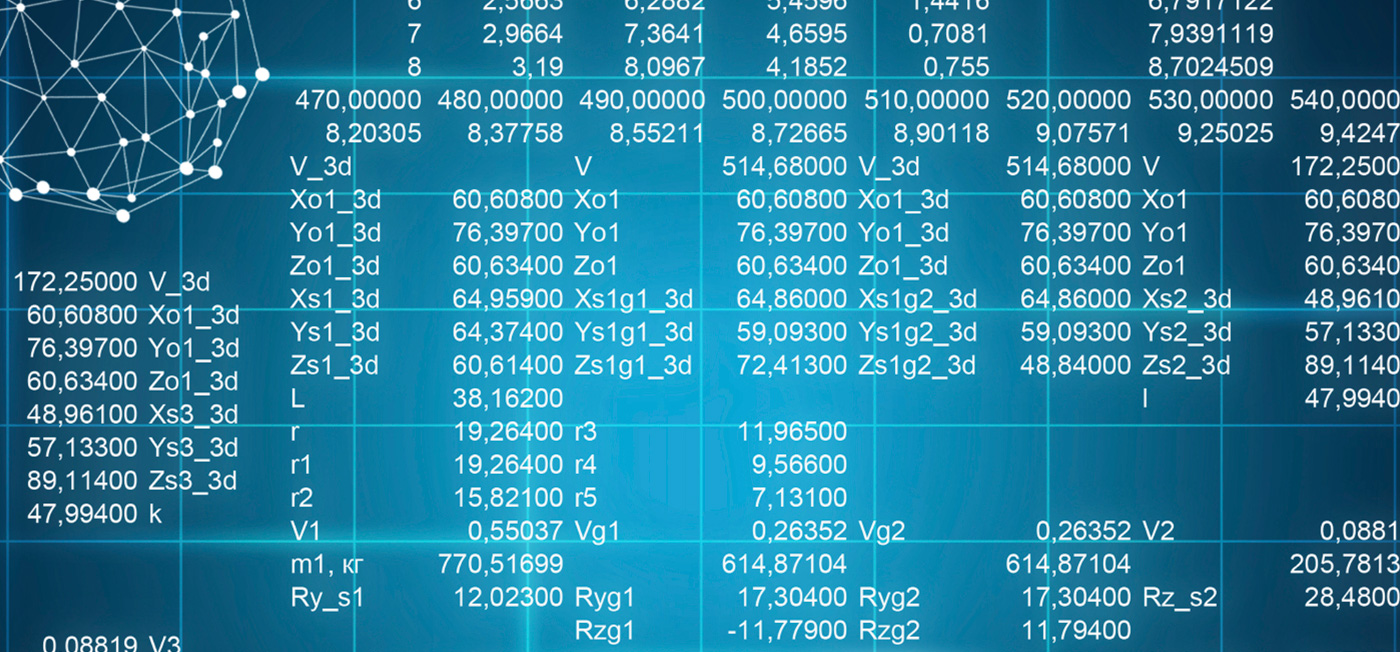

Because IRON LIBERTY used a VPN to access systems, CTU researchers were only able to piece together a partial view of the information the threat actors stole from compromised networks. Examination of leftover artifacts in the Karagany malware folder structure revealed file listings and key logs on victims' systems. The nature of the documentation indicates that IRON LIBERTY has a broad interest in energy generation and supply, as well as defense projects. Some of the victimology suggests that individuals might have been targeted based on Active Directory role descriptions or relationships with other victims, rather than being targeted based on the threat actors' knowledge of the organizations' structure or personnel.

Conclusion

IRON LIBERTY took a hiatus after a series of public disclosures of its infrastructure and tools. However, by 2017 it re-emerged as a significant threat, particularly to the energy sector.

The IRON LIBERTY intrusion patterns observed by CTU researchers describe two very different operations. The first uses minimal tools to maintain access to a target network, with persistence achieved by ensuring a feed of password hashes that can then be replayed against single-factor remote access solutions. The second pattern is more indicative of a full-blown intelligence operation, using a variety of malware and tools and targeting and exfiltrating data for espionage purposes. Some of these tools can be traced back as far as IRON LIBERTY's pre-2014 activity.

Due to the differences between the CASTLE campaign, which follows the first pattern, and other IRON LIBERTY activity, some third parties categorize the perpetrators of the CASTLE campaign as separate from IRON LIBERTY. However, the shared targeting of the energy sector (particularly ICS companies), and the similar techniques (particularly the use of energy industry SWCs) used by the CASTLE campaign and pre-2014 IRON LIBERTY activity led CTU researchers to link CASTLE to IRON LIBERTY.

IRON LIBERTY's tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and time-tested arsenal of advanced capabilities have resulted in successful and operationally secure intrusions that span long time periods. CTU analysis indicates that the threat group continues to enhance existing tools (e.g., Karagany) while developing new tools (e.g., MCMD) to support its objectives. While ICS has been a primary focus of the group's operations, IRON LIBERTY also conducts espionage activities to obtain a wide range of information. The group poses a threat to the ICS community as well as to the defense, nuclear, and energy sectors.

References

Baird, Sean et al. "Attack on Critical Infrastructure Leverages Template Injection." Cisco Talos. July 7, 2017. https://blog.talosintelligence.com/2017/07/template-injection.html

Byrne, Michael. "Hackers Launch All-Out Assault on Norway's Oil and Gas Industry." Motherboard. August 31, 2014. https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/bmjdmd/hackers-target-300-norwegian-oil-and-energy

Dragos. "ALLANITE." May 10, 2018. https://www.dragos.com/blog/20180510Allanite.html

National Cyber Security Centre. "Advisory: Hostile state actors compromising UK organisations with focus on engineering and industrial control companies." April 5, 2018. https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/alerts/hostile-state-actors-compromising-uk-organisations-focus-engineering-and-industrial-control

Secureworks. "MCMD Malware Analysis." July 11, 2019. https://www.secureworks.com/research/mcmd-malware-analysis

Secureworks. "Updated Karagany Malware Targets Energy Sector." July 11, 2019. https://www.secureworks.com/research/updated-karagany-malware-targets-energy-sector

Symantec. "Dragonfly: Western Energy Companies Under Sabotage Threat." June 30, 2014. https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/dragonfly-western-energy-companies-under-sabotage-threat-energetic-bear

Symantec. "Dragonfly: Western energy sector targeted by sophisticated attack group." October 20, 2017. https://www.symantec.com/blogs/threat-intelligence/dragonfly-energy-sector-cyber-attacks

US-CERT. "Russian Government Cyber Activity Targeting Energy and Other Critical Infrastructure Sectors." March 15, 2018. https://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/alerts/TA18-074A

[Footnote: We also suggest reading the CTU blog titled Own The Router, Own The Traffic: As threat actors increasingly target supply chains, man-on-the-side techniques introduce another layer of complexity that organizations must consider, June 24, 2019.]