Summary

In 2017, Secureworks® Counter Threat Unit™ (CTU) researchers continued to track GOLD SKYLINE, a financially motivated Nigerian threat group involved in business email compromise (BEC) and business email spoofing (BES) fraud. During the investigation, CTU™ researchers discovered a previously unidentified BEC group that they have named GOLD GALLEON.

Unlike other BEC groups, GOLD GALLEON does not target a wide range of businesses but appears to focus solely on global maritime shipping businesses and their customers. CTU researchers estimate that between June 2017 and January 2018, GOLD GALLEON attempted to steal a minimum of $3.9 million U.S. dollars from maritime shipping businesses and their customers. The threat actors' theft attempts average $6.7 million per year.

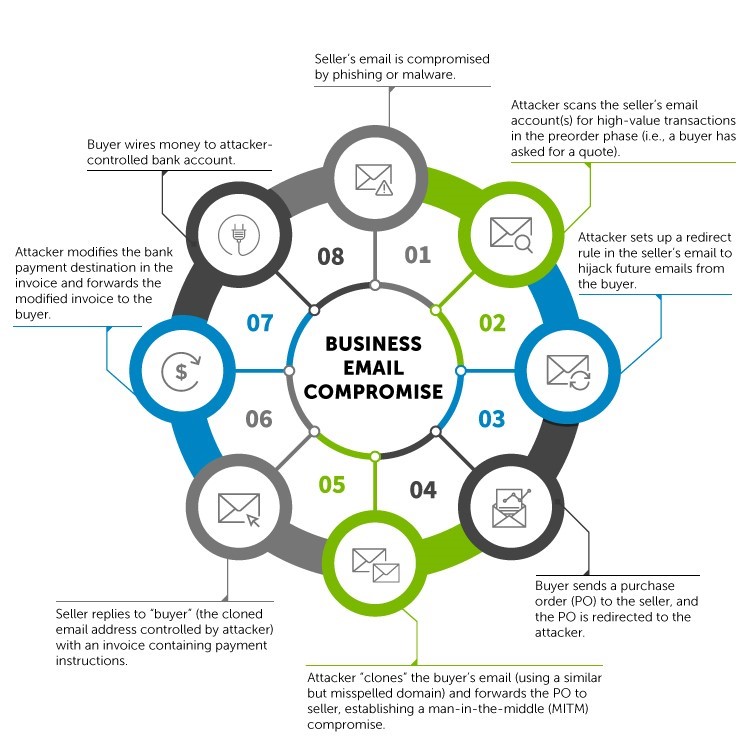

BEC is a social engineering scheme where threat actors gain access to a business's email account. The actors typically use spearphishing emails with attached malicious payloads to steal the email credentials of individuals responsible for handling business transactions. Once the threat actors have obtained these credentials, they can intercept emails between the two parties involved in a transaction and modify financial documents to direct funds to attacker-controlled bank accounts. BEC and BES scams might seem unsophisticated, but they continue to account for significant losses globally. For example, the FBI reported that BEC and BES accounted for estimated losses of $5.3 billion between October 2013 and December 2016.

Key points

- GOLD GALLEON is a BEC threat group likely based in Nigeria.

- The group targets maritime shipping organizations, including companies that provide ship management services, port services, and cash to master[1] services.

- Companies involved in shipping industries are typically globally dispersed and operate in different time zones, meaning that they are often entirely reliant on email for conducting business transactions. Some maritime shipping businesses are therefore susceptible to BEC fraud methods.

- The group uses a range of commodity remote access tools that have keylogging and password-stealing functionality to steal email account credentials.

- The group routinely tests malware on its own systems and tracks detection rates via online virus scanners (e.g., NoDistribute).

- As of this publication, CTU researchers have helped to interrupt multiple GOLD GALLEON fraud attempts, averting losses of more than $800,000.

Who is GOLD GALLEON?

Over the course of the investigation into GOLD GALLEON, CTU researchers have been able to develop unique and detailed insight into the threat group: how it operates, where it is based, and its likely affiliations. GOLD GALLEON is a collection of at least 20 criminal associates that collectively carry out BEC campaigns. The group appears to specifically target maritime organizations and their customers. CTU researchers have observed GOLD GALLEON targeting firms in South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Philippines, Norway, U.S., Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Colombia. The threat actors leverage tools, tactics, and procedures (TTPs) that are similar to those used by other BEC/BES groups that CTU researchers previously investigated (e.g., GOLD SKYLINE). The groups have used the same caliber of publicly available malware (inexpensive and commodity remote access trojans (RATs)), crypters, and email lures.

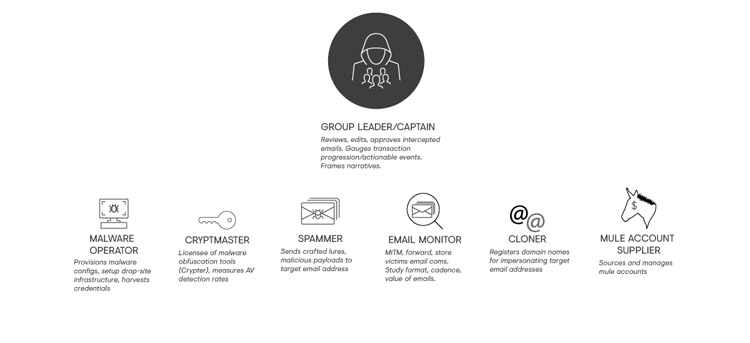

The group appears to have a loose organizational structure, with activities coordinated by several senior individuals. Tasks are allocated to individuals in the group; for example, one group member may have responsibility for obfuscating the group's RATs with crypters, while others are tasked with monitoring victims' email for business transactions that are about to be invoiced. Some senior members often handle the purchasing of malware, crypters, and infrastructure, and they frequently experiment with alternative tools. CTU researchers also observed senior members coaching and mentoring less-experienced group members and liaising with external providers of related criminal services (e.g., suppliers of mule accounts for transferring stolen funds and crypter sellers; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Organizational diagram of GOLD GALLEON threat group. (Source: Secureworks)

GOLD GALLEON uses the Hide My Ass! (HMA) proxy and similar privacy services to disguise its origin. Several data points identified by CTU researchers suggest that it is highly likely that GOLD GALLEON is based in Nigeria:

- Visibility of the actors' systems suggest that many were regularly connecting to the Internet via Nigeria-based infrastructure.

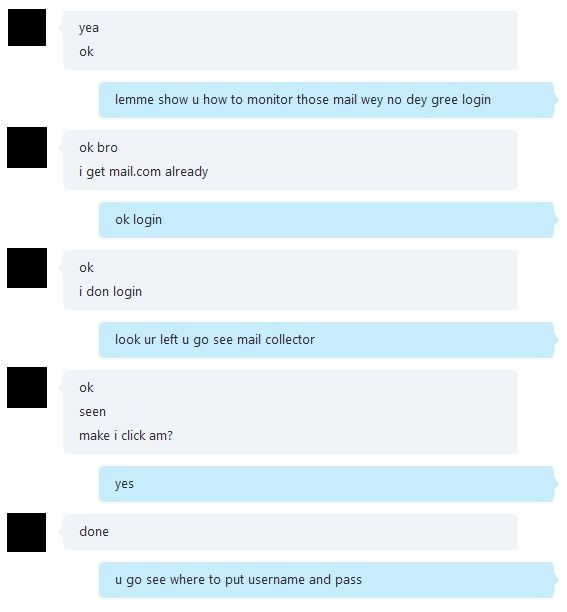

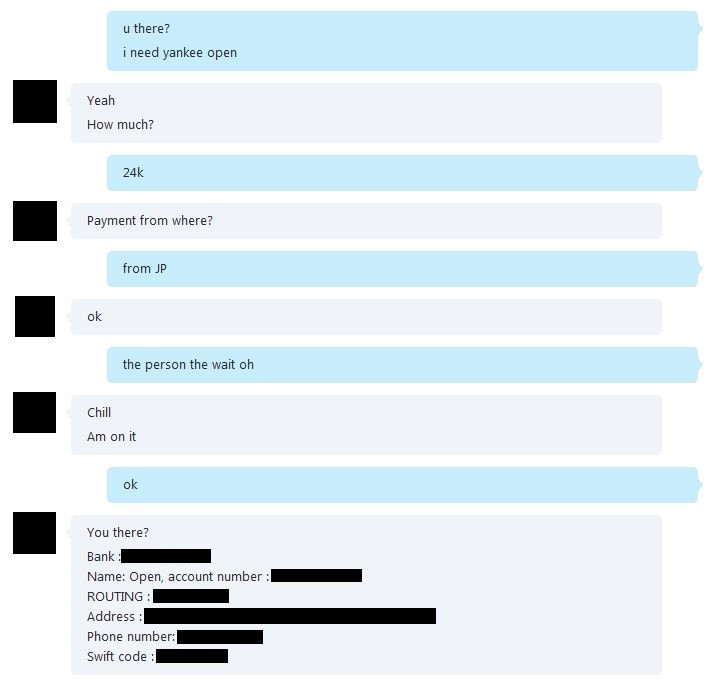

- The GOLD GALLEON crewmembers communicate regularly using instant messenger services such as Skype. Observed conversations between crewmembers were in Nigerian Pidgin English (see Figure 2). Pidgin is a simplified form of speech that is usually a mixture of two or more languages, has a rudimentary grammar and vocabulary, and is used for communication between groups speaking different languages. Appendix A shows additional examples of Nigerian Pidgin phrases commonly used by GOLD GALLEON.

Figure 2. Example of conversation between the group leader and a crewmember. (Source: Secureworks) - CTU researchers' visibility of the group's usernames, passwords, and other artifacts suggest a strong link between members of GOLD GALLEON and a popular fraternity in Nigeria dubbed the Buccaneer Confraternity (see Appendix B).

Links to the Buccaneer Confraternity

Many of the GOLD GALLEON conversations observed by CTU researchers used phrases, usernames, and passwords that linked to the Buccaneer Confraternity group. Keywords such as "awumen," "alora," "Sealords," and "1972buccaneer" in context reference the confraternity. One GOLD GALLEON actor also used a Buccaneers Confraternity logo on an online account (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Variant of the Buccaneers Confraternity logo. (Source: Secureworks)

The Buccaneers Confraternity was originally established to support human rights and social justice in Nigeria. Reports suggest that a small subset of the group (often referred to as a cult) may engage in criminality, which offers a potential explanation for GOLD GALLEON's apparent links to the Buccaneer Confraternity movement.

How does GOLD GALLEON operate?

GOLD GALLEON displays similar tradecraft to other Nigerian-based BEC groups observed by CTU researchers. The group follows a common operational pattern often relying on low-tier, free, or inexpensive tools. What it lacks in technical prowess is made up for in social engineering, agility, and persistence. Despite technical challenges and minimal investments in cybercrime tools, infrastructure, and automation, the group's profit margins are orders of magnitude greater than its initial investment.

Reconnaissance

CTU researchers assess that GOLD GALLEON identifies target email addresses by conducting reconnaissance of publicly available contact information (e.g., a company's website). The actors may leverage commercially available marketing tools that scrape email addresses from company websites (e.g., Email Extractor, BoxxerMail). CTU researchers found evidence that suggests these threat actors occasionally purchase email lists of target businesses. In order to acquire new victims after gaining entry into a target's inbox, the threat actors use a free tool called EmailPicky to extract the target's contacts from their address book, as well as every email address with which the target has had an exchange. Many of the harvested contacts are in the maritime shipping industry, so this tactic can be extremely fruitful for the threat actors.

Attacker TTPs/attribution

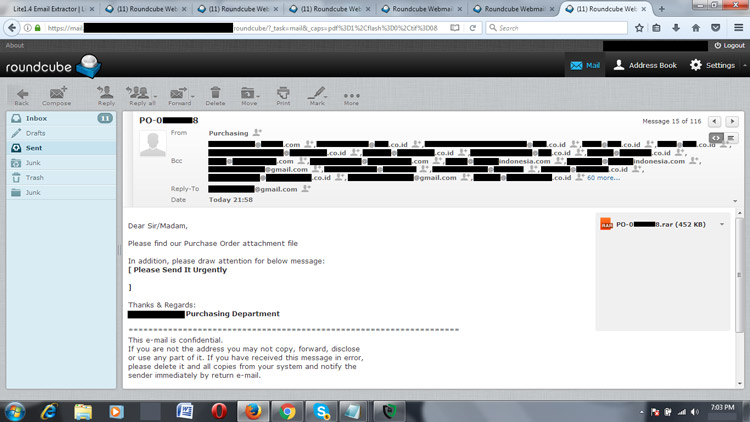

Similar to other BEC threat groups, GOLD GALLEON uses spearphishing emails with malicious attachments to compromise its victims (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. GOLD GALLEON crewmember crafting a phishing email. (Source: Secureworks)

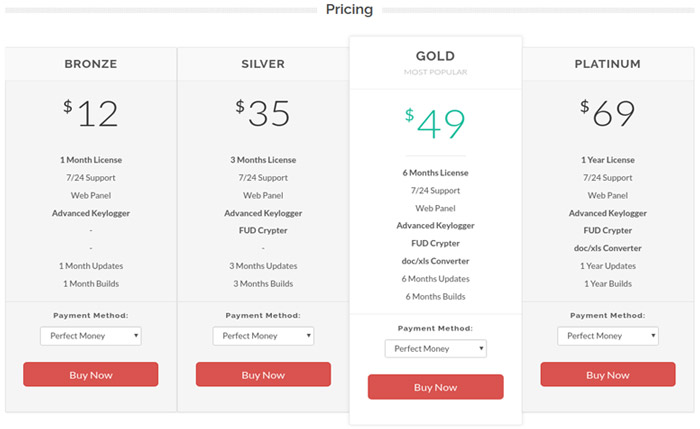

The spearphishing emails are created with the intended recipient in mind, in this case focusing on shipping topics. When opened, attachments deploy a RAT that has keylogging and password-stealing functionality. Tools deployed by GOLD GALLEON include the Predator Pain, PonyStealer, Agent Tesla, and HawkEye keyloggers. All of the malware leveraged by GOLD GALLEON is readily available from online hacking markets. For example, the cost for the Agent Tesla RAT is between $12 and $69, depending on the support levels provided (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Agent Tesla malware service-level tiers. (Source: Secureworks)

Actions on objectives

Once the GOLD GALLEON crew compromises the business email accounts of a company's employees, crewmembers monitor the employees' inboxes to identify emails for ongoing business transactions. In a typical BEC scam (see Figure 6), an attacker compromises a seller's email account to position themselves as a "man-in-the-middle" between the seller and a buyer in an existing business transaction. The threat actor then uses their control of the seller's account to passively monitor the transaction. When it is time for payment details to be relayed to the buyer via an invoice, the threat actor intercepts the seller's email and changes the destination bank account on the invoice to the attacker's money mule account. If the revised payment account does not appear to be suspicious, the buyer will likely submit the payment.

Figure 6. Typical BEC process. (Source: Secureworks)

CTU researchers observed GOLD GALLEON threat actors successfully submitting fraudulent invoices to buyers while a business transaction was in progress. The altered invoices were modified from genuine versions created by the seller that were available in the seller's email account. The threat actors were in control of the seller's email account and were monitoring email traffic, but the buyer was not likely to question the invoice because it appeared to contain correct and familiar information. Only the bank details where the money was to be wired were changed.

Cloned domains and look-alike email addresses

In order to impersonate a buyer or seller in a particular transaction, GOLD GALLEON and other BEC groups have purchased domains that closely resemble the buyer or seller's company name, also known as "cloning." CTU researchers have also observed BEC threat actors registering email accounts that contain a variation of the target's name (e.g., john . doe @ gmail . com or jdoe @ gmail . com. With these look-alike domains and/or email addresses in hand, the cybercriminals can impersonate either party.

Disrupting the adversary — Incident case studies

The cybersecurity industry clearly has a role to play in disrupting these threats. While investigating the activities of GOLD GALLEON and another BEC group conducting fraud against the shipping industry, CTU researchers were able to interrupt dozens of BEC fraud attempts. Victim notifications prevented some fraudulent transfers, and identification of attacker-controlled accounts enabled banks to stop fraudulent use.

The following case studies offer additional insight into GOLD GALLEON's methods and also highlight some of the challenges when disrupting these threats.

Case study 1: Thanks, but we already know… we just don't know how.

One of the companies that GOLD GALLEON compromised was a shipping company based in South Korea. The threat actors were able to steal credentials for eight different email accounts, including an account for one of the company's accountants. With this access, GOLD GALLEON targeted all of the company's clients. The threat actors monitored the South Korean company's business email day and night and became very familiar with the company's billing cycles, clients, and various business deals.

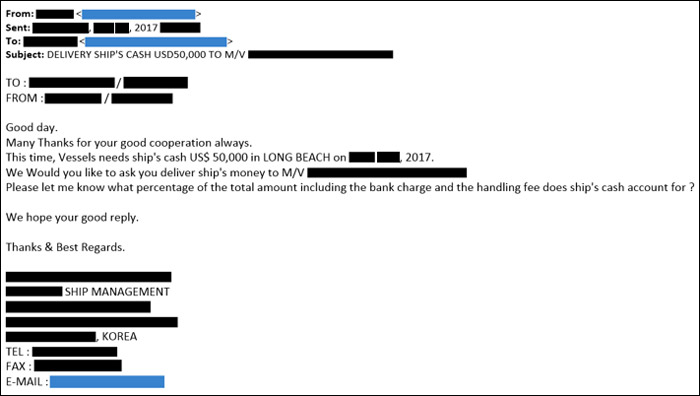

Not long after CTU researchers began tracking GOLD GALLEON, the threat actors were monitoring a business transaction where the South Korean shipping company was requesting "cash to master" (CTM) services for a ship arriving in the U.S. The South Korean company sent an email to the U.S.-based CTM organization requesting delivery of the approximately $50,000 in crew's wages and clarification of the total payout fee (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Cash to master (CTM) request from the South Korean ship management company. (Source: Secureworks)

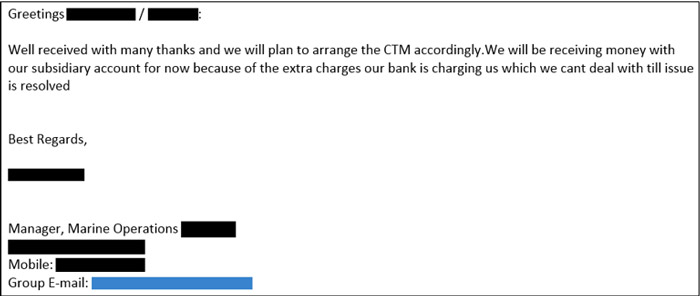

To insert themselves into the transaction, GOLD GALLEON threat actors set up an Outlook email account using the name of an employee working for the CTM company and sent a fraudulent email. The message requested that the South Korean company submit payment to the CTM's "subsidiary [bank] account," because the CTM was purportedly working to resolve an issue with their regular bank regarding extra fees (see Figure 8). The provided account details were for a mule account used by GOLD GALLEON.

Figure 8. GOLD GALLEON actors impersonating a shipping agent to coerce the South Korean ship management company into diverting funds to the attacker-controlled bank account. (Source: Secureworks)

Aware that the South Korean company was potentially about to send $50,000 to the threat group and not to the intended provider of ship services, CTU researchers notified the U.S. company as quickly as possible. Separately, the South Korean shipping company had been in touch with the U.S. shipping agent to verify that the subsidiary account payment details were correct, so the U.S. shipping agent was already aware of the fraud attempt. However, the agent did not know how the South Korean company had received the altered bank account details. CTU researchers were able to complete the picture for them.

Case study 2: If at first you don't succeed…

When CTU researchers detected the GOLD GALLEON crew attempting to defraud another one of the South Korean company's clients for $325,585, they notified the potential victim. The client, a large Japanese company with clients in the Far East and the Southeast Asian regions, provides marine transportation of petroleum products, chemicals, and other liquids. CTU researchers notified the Japanese company and explained the ongoing fraud attempt. The company was aware of the situation, as they judged that the payment request was suspicious. Despite the failed attempt, the GOLD GALLEON actors repeated their attempt using a forged invoice on the South Korean company's letterhead.

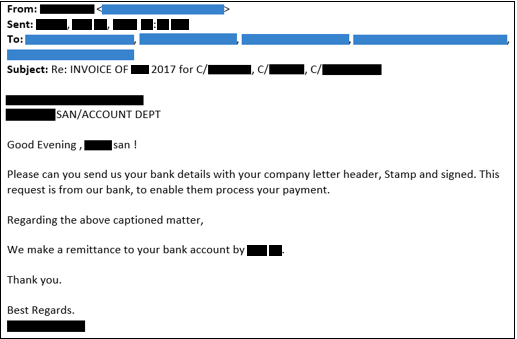

This was a common tactic the GOLD GALLEON crew used to try and fool the clients of the South Korean shipping company. The GOLD GALLEON threat actors were able to obtain a copy of the Korean shipping company's corporate letterhead by impersonating the Japanese marine transportation company. They stated in their email request that they needed to present it to their bank to process payment for the South Korean company's services (see Figure 9). The South Korean company obliged and sent them an electronic copy, which the threat actors continued using for future spoofed correspondence with many of the company's clients.

Figure 9. Spoofed email from GOLD GALLEON requesting official company letterhead of a South Korean shipping company for use in future fraud schemes. (Source: Secureworks)

Case study 3: Third time's a charm

A week after the fraud attempt on the Japanese marine transportation company, CTU researchers detected GOLD GALLEON attempting to steal $234,834 owed to the South Korean shipping company by another client: a large multinational Japanese conglomerate. In response, CTU researchers notified both parties, as well as the bank where the mule account due to receive the stolen funds was located.

GOLD GALLEON had used the spoofed email address of the South Korean company's accountant and sent a request to the Japanese conglomerate on the company letterhead to remit payment of the $234,834 to the attacker-controlled bank account. In this particular instance, the Japanese conglomerate was suspicious when they received the request to change payment to an alternate bank account. However, only with the additional context provided from the CTU researchers' notification were they able to understand the full nature of the risks they were facing.

Additionally, CTU researchers reached out to the South Korean CERT (KN-CERT) so it in turn could notify the South Korean company of the nefarious activity and help them mitigate the threat on their network. KN-CERT also helped the South Korean shipping company implement security measures to monitor and help protect their business email from being compromised in a similar way in the future.

Conclusion

By disclosing details of the GOLD GALLEON threat, its capabilities, and its approach to conducting BEC-related fraud, CTU researchers are trying to provide a greater understanding of the BEC threat and why these campaigns continue to be so lucrative. As evidenced in this report, the monetary losses can be significant to the victims and the affected businesses. In some cases, the victims are unaware of what is happening until it is too late. Organizations in some industries (in this case shipping) may be exposed to heightened risk as threat actors focus their attempts toward industries that are more susceptible to these techniques. CTU researchers encourage organizations to evaluate the BEC threat in the context of their own systems and consider the following steps to mitigate the risks associated with BEC:

- Implement two-factor authentication (2FA) for corporate and personal email. Small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) are popular targets for BEC groups because SMBs typically have limited security budgets. Most BEC threat actors rely on remote access to a company's email via commodity webmail programs, so 2FA would deter all but the most sophisticated attackers.

- Inspect the corporate email control panel for suspicious redirect rules. An unexplained redirect rule that sends incoming email from specific addresses to third-party systems could indicate a compromise and should trigger an organization's incident response process.

- Carefully review wire transfer information in suppliers' email requests to identify suspicious details.

- Always confirm wire transfer instructions with designated suppliers using a previously established non-email mode of communication, such as a fax number or phone number. Establish this communication channel using a method other than email.

- Require multiple approvals for wire transfers, and ensure this procedure is difficult for cybercriminals to discover.

- Question any changes to typical business practices and designated wire transfer activity (e.g., a business contact suddenly asking to be contacted via their personal email address or a change to an organization's designated bank account information).

- Be suspicious of pressure to take action quickly and of promises to apply large price discounts on future orders if payment is made immediately.

- Thoroughly check email addresses for accuracy and watch for small changes that mimic legitimate addresses, such as the addition, removal, substitution, or duplication of single characters in the address or hostname (e.g., [email protected] versus username@ examp1e.com).

- Create detection rules that flag emails with extensions that are similar to company email addresses (e.g., abc_company versus abc-company).

- Limit the information that employees post to social media and to the company website, especially information about job duties and descriptions, management hierarchy, and out-of-office details.

- Consider adopting the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) standards to deter money laundering and fraudulent wire transfers.

- Consider using the free pdfxpose tool that CTU researchers developed to help detect wire-wire fraud. CTU analysis of GOLD SKYLINE activity revealed that the threat actors edited PDF invoice files by redacting the original payment details with a white opaque rectangle and then overlaying it with the money mule account information. This tool searches for sub-page-sized opaque rectangles with text overlays and adjusts the opacity and color to reveal potentially suspicious edits.

Appendix A — Nigerian Pidgin conversations

Figure 10. Conversation between the leader of the GOLD GALLEON group and a crewmember. (Source: Secureworks)

Figure 11. High-level GOLD GALLEON crewmember speaking with group leader about a BEC scam. (Source: Secureworks)

Figure 12. GOLD GALLEON crewmember asking contact for a U.S.-based open beneficiary bank account. (Source: Secureworks)

Appendix B — The Buccaneers Confraternity

The Buccaneers Confraternity is a descendant of the Pyrates Confraternity group (also known as the National Association of Seadogs). According to historical records, the Pyrates Confraternity was founded in 1952 by Nobel-prize winning author Wole Soyinka and six of his friends (see Figure 13). The first chapter was formed on the campus of University College Ibadan, a prestigious institution and one of the oldest universities in Nigeria. The confraternity was conceived as a response to class privilege, elitism, and other perceived social injustices against poorer students at the university. Membership was open to male students who were academically bright, regardless of their tribe or religion. The anti-establishment group adopted the motto "Against all conventions" and the classic Jolly Roger skull and crossbones pirate flag as its logo. Members went by names such as "Cap'n Blood" and "Long John Silver." The organization's ceremonies and customs revolve heavily around pirate symbology. The Pyrates Confraternity became the only confraternity on Nigerian campuses for almost 20 years.

Figure 13. The "Original Seven" founding members of the Pyrates Confraternity in pirate costumes. (Source: https://www.nas-int.org/about-nas/history)

In 1972, a schism took place when Pyrate Bolaji Carew led a "mutiny" against the confraternity. Dissatisfied with the conduct of the organization, he and several other members formed a rival group known as the Buccaneers Confraternity, borrowing many of the structures, ceremonies, and symbology from the Pyrates Confraternity. Because of this fracture, the Pyrates registered the name "National Association of Seadogs," while the Buccaneers refer to themselves as "Sea Lords."

Over the years, infighting led to further factions and spin-off groups, resulting in dozens of organizations. While some of the older confraternities focus on humanitarian efforts, subsequent splinter groups have strayed from those traditional values. The groups are often referred to as "campus cults," and students are warned about the dangers of joining them. Many exhibit gang-like activity and align with local militant groups. They have engaged in armed robbery, kidnapping, operating prostitution rings, and cybercrime.

[1] Cash to master services involve a representative from a cash to master company meeting a ship upon its arrival into its destination port and paying the ship's captain, who then pays crewmembers their wages, historically in cash accompanied by armed guards. In exchange, the cash to master company receives a service fee.

Secureworks has been acquired by Sophos. To view all new blogs, including those on threat intelligence from the Counter Threat Unit, visit: https://news.sophos.com/en-us/.